Do you sometimes wonder what the world will sound like in a hundred years?

What our children’s children will dance to, what lullabies will soothe them to sleep, and what sounds will tell them who they are?

The music we know today – the viral hits, the TikTok remixes, the auto-tuned anthems – will one day fade into forgotten pieces of history, buried somewhere in digital archives where just a few will bother to access. But some sounds deserve to exist. The ones bigger than fame or trend. The ones that hold memory.

I am talking the hum of a mother’s lullaby. The rhythm of clapping games under the sun. The echo of folktales sung on red earth and retold under moonlight. These are not just songs; they are timekeepers.

In this era where everyone’s chasing what’s next, Dinachi is reaching for what came before.

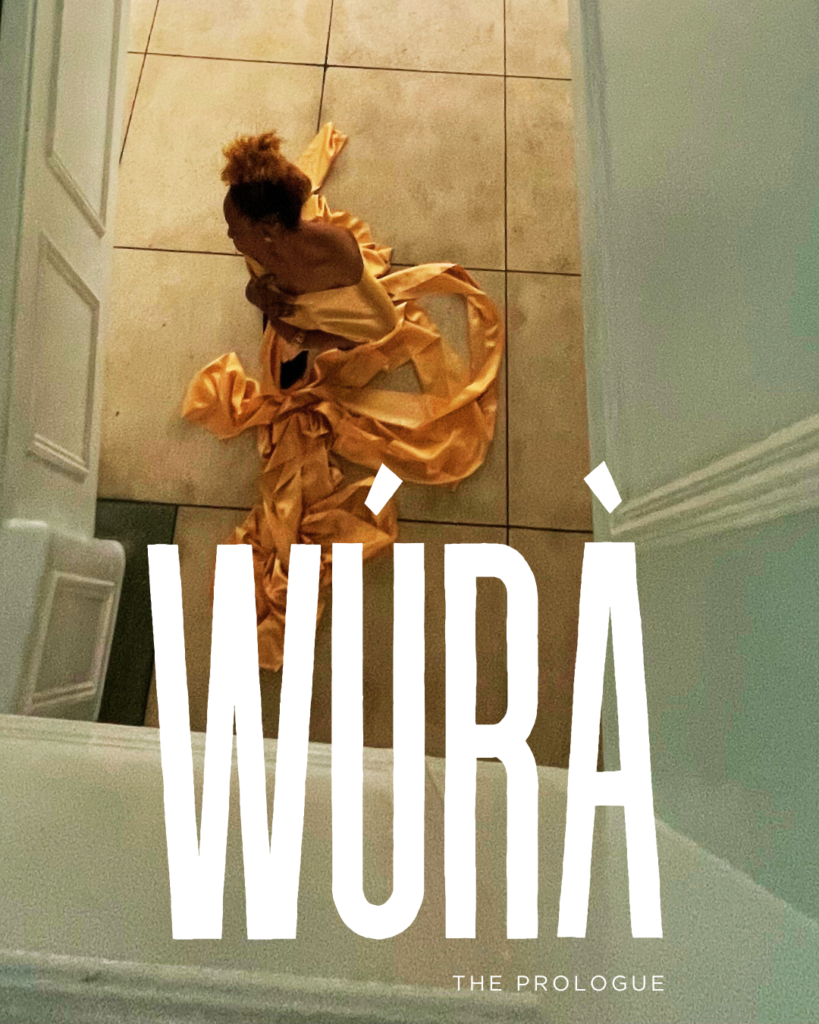

Her latest body of work, The Wúrà Project, is not a chase for radio play or streaming charts. It is a quiet act of preservation: an acoustic archive of songs that shaped Nigerian childhoods long before hashtags or hit singles. In an age where music often feels disposable, Dinachi’s approach feels sacred.

A five-track collection that took two years to make, The Wúrà Project features “Akwukwo Na Ato (Bata Mi A Dun Kokoka),” “Iya Ni Wura,” “Onye Mere / Do Ki Salama,” “Omode Meta Sere (Ojo n Ro),” and “Omo Oni Kelede.” Each song draws from a different part of Nigeria (Igbo, Yoruba, Hausa, Bini, Igala, and Urhobo), weaving together into sounds that feel both familiar and new. The melodies are tender and minimalist, stripped of excess, and carried by the sincerity of Dinachi’s voice.

It is, at its core, a work of love. “My kids were growing up in London and don’t have the same experiences I had,” she says softly. “I wanted to share that part of my growing up with them.” That simple desire to connect her children to the songs that raised her became the heartbeat of The Wúrà Project.

“Our cultures are important, and our heritage is our treasure,” Dinachi adds. The conviction in her voice is unwavering. For over a decade, she has been an artist, but Wúrà demanded something different: patience, research, memory. She spent months speaking with older people who still remembered fragments of the songs, piecing together verses and meanings that time had almost erased. Each conversation felt like opening a window into the past.

The result is an album that feels alive with history, yet deeply personal. In Iya Ni Wura, she honours Yoruba mothers, their sacrifices rendered in melody and warmth. Onye Mere / Do Ki Salama becomes a dialogue between cultures, blending Igbo and Hausa in a joyful melody. Omode Meta Sere (Ojo n Ro) captures the innocence of children’s play, while Akwukwo Na Ato nods to learning and the simplicity of early life. The closing track, Omo Oni Kelede, dances with nostalgia: playful, familiar, and grounding.

There is something profoundly grounding about the project. It’s the kind of music you can play at home, around children, or when you need to feel the weight of stillness again. It is soft without being fragile, cultural without being performative, intimate without being indulgent. In Dinachi’s words, “Our history is important. We need to remember where we’re from. It’s our identity.”

These songs, beautiful as they are, do not belong to Dinachi alone. They belong to all of us — Nigerians, Africans, and the diaspora — who grew up humming their melodies without knowing their origins. These are communal songs, inherited not from individuals but from generations. They are the music of memory, credited to no single author, yet carried in countless hearts.

And that’s what makes The Wúrà Project even more powerful: it’s not just an album; it’s a collective heirloom. In rebirthing these folk songs, Dinachi is reminding us that our shared history deserves a place in the present. That what was once oral tradition can now live forever through sound.

In listening to The Wúrà Project, you get the sense that Dinachi is doing something larger than making music. She’s restoring memory, building a bridge between what was and what could still be. Her sound resists categorisation. It’s not mainstream pop or strict folk. It’s something else entirely, an ancestral modernism: a space where tradition meets self-expression, where the old and the new breathe together in harmony.

“It’s important for me to enjoy and like what I’m doing,” she expresses. “And this feels like home.” There’s something beautiful in that: the idea that creativity can also be an act of cultural service. That by preserving what came before, an artist can help us all remember who we are.

Wúrà means gold in Yoruba, and that’s exactly what Dinachi has unearthed: gold in memory, gold in simplicity, gold in the act of remembering.

Listen to The Wúrà Project and reconnect with the songs that raised us.

Out now on all platforms.