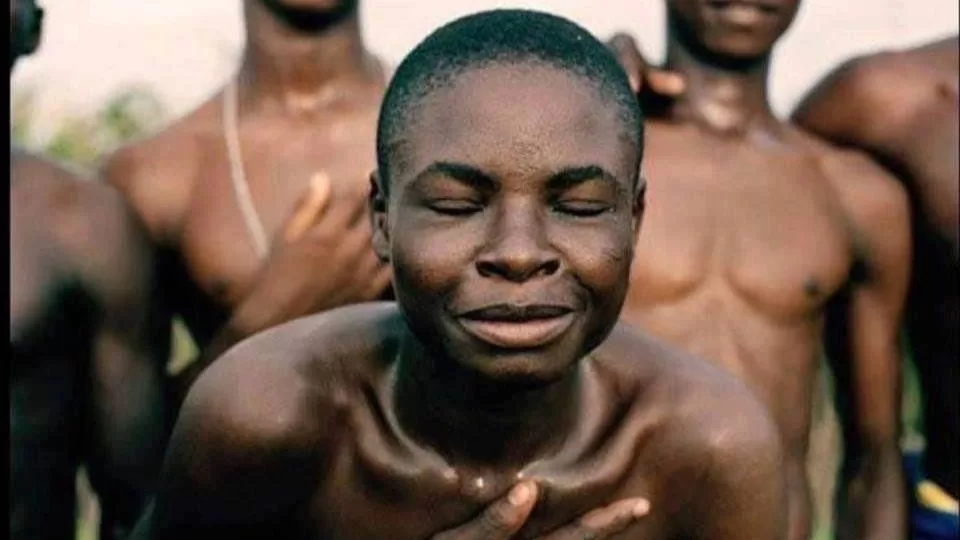

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is a study in restraint. It uses stillness and careful observation to address grief and complicity without turning them into a spectacle. The film’s honesty feels unsettling because it does not shy away from hard truths.

Directed by Zambian-Welsh director Rungano Nyoni, the film examines silence, grief, and complicity within family and society. It explores how trauma is buried, normalised, and passed down, particularly in private spaces that should feel safe. The film’s power comes not from what it shows, but from what it withholds.

The story follows Shula, a young woman who discovers her uncle’s body late one night on a deserted road. This discovery becomes the quiet trigger for a family funeral that stretches across several days. As rituals unfold, the film reveals how death can expose truths that life demands be hidden.

Susan Chardy’s performance as Shula is measured and profoundly affecting. She plays the character with a stoicism that feels more like survival than emotional absence. Her stillness serves as a form of resistance in a family that insists on surface-level harmony.

Opposite her is Elizabeth Chisela as Nsansa, Shula’s cousin, whose chaotic energy disrupts the film’s calm exterior. Nsansa is loud, volatile, and emotionally unfiltered. The contrast between the two women reflects the different ways people respond to shared trauma.

Nyoni’s direction is precise and deliberate. She favours long takes, minimal dialogue, and everyday interactions that slowly take on meaning. The camera lingers on faces, gestures, and silences, allowing the audience to confront discomfort rather than escape it.

The film’s approach to trauma is especially striking. Abuse and harm are never sensationalized or explicitly shown. Instead, they are present in the reactions, pauses, and the collective choice not to speak. This absence becomes a form of violence.

Funeral rituals play a central role in the film’s structure. What should be a space for mourning turns into a performance of denial. The insistence on respect, tradition, and family unity serves to suppress truth rather than honour it.

The title itself carries symbolic weight. The guinea fowl is known for its loud call, a warning of danger. In this film, the call is muted. Silence replaces alarm, and the cost of that silence becomes painfully clear.

Visually, the film is careful and composed. The cinematography avoids excess, using natural light and lived-in spaces. There is a quiet tension in the images that reflects the emotional weight the characters carry.

Sound design is used sparingly, allowing silence to convey more than music could. When sound does enter the frame, it often feels intrusive, highlighting moments when the characters face unavoidable confrontation.

What makes On Becoming a Guinea Fowl especially significant is its place within contemporary African cinema. It resists spectacle and does not seek to explain itself for easy consumption. Instead, it embraces emotional and moral discomfort, trusting the audience to engage with its complexity.

This is African storytelling that looks inward. It addresses private harm, generational silence, and the quiet agreements that let abuse continue. It challenges the idea that African films must be loud, dramatic, or overtly political to matter.

The film is not interested in closure or catharsis. It does not provide neat resolutions or comforting answers. Instead, it offers recognition—the kind that lingers and unsettles.

By the time the film ends, its impact feels cumulative rather than explosive. The weight of what has remained unsaid settles heavily. It stays with you because it mirrors realities many recognize but rarely confront.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is not an easy watch, but it is a necessary one. It reminds us that silence is never neutral; it is a choice and often, a deeply harmful one.

Quiet yet piercing, restrained yet emotionally devastating, the film sets a high bar for thoughtful cinema. It confirms Rungano Nyoni as a filmmaker unafraid of discomfort. This is a work that lingers long after the final scene and feels essential in conversations about the future of African cinema.