In Nigeria, the anarchy never stops. Inflation surges. The naira depreciates. Gas lines snake around cities like festering wounds. Politicians half-apologise or not at all. And yet Nigerians laugh. Not because things are good but because laughter is a survival necessity, a way to get through a system that sometimes appears designed only to kill you.

Memes are not just jokes. They’re an emotional archive. A living record of community strength. They’re asserting, “We’re looking at the mess, we’re in the mess, and we’re not going to let it overwhelm us.”

Comedy as camouflage

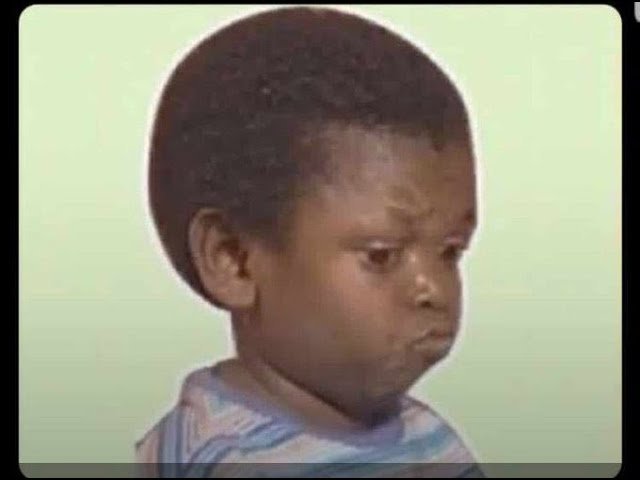

Based on how fast memes start making the rounds, you can always be certain that something terrible has happened in Nigeria. A hypocrisy of a new economic initiative, a bullying encounter with the police, or even a poorly executed tweet by the government is promptly flipped on its side into world jokes. A malfunctioning ATM is a national malfunction indicator. A Nollywood slapstick clip is the optimal response to breaking news of a hike in fuel prices.

READ MORE: 50 Romantic And Flirty Good Morning Messages For Him

The humour is never reassuring. It’s blunt, typically merciless, and spiced with irony. It doesn’t console but nakedly exposes. It mocks the system. It identifies the helplessness. And most importantly, it reminds them that they are not alone. That someone else somewhere is just as downtrodden, just as weary, just as laughing instead of wailing.

Memes as protest tools

In October 2020, amid #EndSARS protests, memes joined the battle. When Nigerians protested against police brutality, they also swamped the internet with jokes, caricatures, and edits against the government. One minute, they’d have live updates of protest locations. The next was a meme of a government politician photoshopped into a clown suit. It was strategic: the memes exaggerated anger but wrapped it in humour.

Online, activists felt like they were being watched. Memes gave them a kind of cover, masking sharp, biting critique behind something that looked like playfulness. But to insiders, the message was unmistakable. Protesters weren’t just fighting with placards. They were fighting with one-liners.

Digital Fela energy

Fela Kuti sang, “Suffer suffer for world / Enjoy for heaven.” It was trenchant. It was tart. It was satire decades before social media. The meme-makers of today are heirs to the same tradition, using humour to voice the pain and using art to resist being erased.

Where Fela had dancers and saxophones, Gen Z had sound bites and screenshots. A trending meme might borrow a Nollywood freeze, a popular TikTok voiceover, or a remixed government statement. It’s a digital protest song, spooling through timelines, reminding everyone that even if you can’t change the country overnight, you can name its madness. And naming is significant.

The psychology of humour and grief

Psychologists call it “humour as a defence mechanism”. Humour keeps people from being intolerable about what otherwise would be unacceptable in high-stress circumstances. For Nigerians, theory doesn’t apply—it’s actuality. The day-to-day weight of living in a country where public infrastructures disintegrate and living from one day to the next isn’t guaranteed can’t constantly be confronted directly.

A meme is often easier than a paragraph. It says, “I’m tired,” without having to explain. It says, “This country is wild,” without breaking into tears. Humour offers temporary relief and, in some cases, the only relief.

Who gets to laugh?

But meme culture is hierarchical as well. Sometimes the joke turns inward, brutally against marginalised groups—queer people, women, and people with low incomes. Then, memes are used to reinforce social violence instead of combating it. The same instrument that liberates can be used to injure.

This is the fine line Nigerian meme culture treads: solidarity and ridicule, survival and spectacle. When employed with sensitivity, it speaks to you. When employed thoughtlessly, it alienates.

A national archive of emotion

Somewhere down the line, Nigeria’s meme culture will be studied by historians just as historians study newspapers and speeches. Jokes such as these—crazy, funny, and overall irresponsible—are records of people’s feelings. They show what people feared, what they hoped for, and what they could no longer possibly seriously consider.

In a country whose headlines are read too often like a bad joke, it is no surprise that the headline would be satire. Humans laugh not because nothing matters but because too much does. The laugh isn’t empty. It’s significant. Full of grief. Full of resolve.

Final word

Memes aren’t going to fix Nigeria. They will not stop an ill policy, nor will they stop the next fuel price hike. But they provide something potent: perspective. And, in most places, peace. Nigerians meme through trauma because it is how they adapt. Because laughter, though fractured, is still resistance.